Contents

“Long ago, man created wine from the fruit of the vine, and he was so proud of his invention that he not only made it an important part of his diet, but also integrated it into his religion, traditions, pleasures and even culture”. said Michel Bouvier. Since ancient times, when viticulture and art met, mankind has paid homage to this elixir of the gods.

In Western Europe, thanks to Dionysus and his Mysteries, wine is even one of the origins of theater and the oratory arts. Moreover, wine is closely linked to art, not only because it is represented in it, but also because it is consumed by artists, and has inspired them for millennia.

(I don’t think it’s worth mentioning, but for the sake of brevity, we’re concentrating on Western Europe in this article).

Wine and art in antiquity

The first links between wine and art were forged around the 5th-6th centuries B.C. via pottery and ceramics, particularly in ancient Greece and Rome. Indeed, jars and amphorae, the containers used to store, transport and serve wine, began to be accompanied by illustrations depicting men or gods interacting with wine. Wine was often presented as a liquid providing numerous virtues, both physical and moral. Many artistic representations of wine were to be found on the amphorae and jars containing it, as well as on the many mosaics found in Roman pavilions and frescoes discovered in Magna Graecia. Of particular interest is the Fresco of the Diver’s Tomb, dated 480-470 BC and found in Paestum. Part of the fresco depicts men sipping wine and offering each other cups of the liquid.

Caption: Detail of an ancient Greek fresco in Paestum, Italy. “Diver’s tomb (© Adobe Stock – Peuceta)

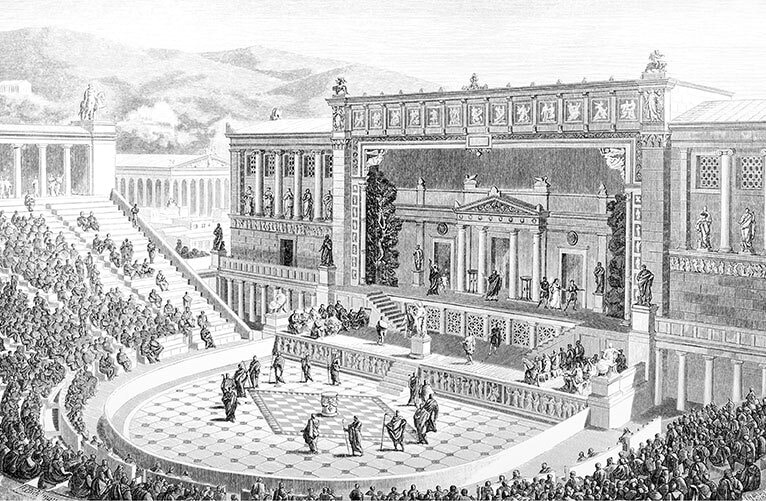

Of course, wine in Antiquity was also and above all Dionysius and the whole world around him. In Greek mythology, Dionysus (Bacchus in Roman mythology) is the god of wine, the vine and its excesses. Dionysus is one of the most important gods of Greek mythology, fascinating people to such an extent that Greek tragedy, the mother of theater, has its roots in the worship of Dionysus and wine. In ancient Greece, between 535 and 532 BC, the tyrant Pisistratus inaugurated the first Dionysia, an annual festival dedicated to Dionysus and wine. These festivities included the first tragic and comic competitions, followed (or preceded) by large-scale popular festivities, during which wine must certainly have flowed freely. From this time onwards, Greek tragedy began to emerge and develop, inspiring all the greatest playwrights in our history (Corneille, Racine, Shakespeare, Jean Anouilh…).

Caption: Victorian engraving of the Theater of Dionysus in Athens (© Adobe Stock – Antiqueimages)

Finally, how can we talk about wine without mentioning the Bible? Even the most atheistic among you are familiar with Jesus’ words, quoted in the New Testament: “Drink from it, all of you, for this is my blood” (Matthew 26:26-29), referring to a cup of wine during his last meal with the twelve apostles on the evening of Holy Thursday. Nor are you unfamiliar with Jesus’ miracles of turning water into wine. In all, the Bible quotes the term wine 443 times, using it most of the time to evoke gladness, fellowship and, of course, drunkenness. Christian literature and iconography (paintings, engravings, frescoes, stained glass…) will be greatly impacted, and many of them will refer to the delicious nectar that is wine. Moreover, Christian ritual arts were soon punctuated by the drinking of liturgical wine by the officiating clergy during mass… and by the faithful present until the 13th century!

Wine and art from the Middle Ages to the French Revolution

Following the fall of the Roman Empire, it was the clergy and their monasteries who revived winegrowing as part of a Eucharistic approach (production of mass wine and the monks’ agricultural work). Throughout the Middle Ages, these same religions were considerable producers of art (literature, illuminations, stained glass, bas-reliefs, sculpture, paintings, construction of sacred buildings…). Unsurprisingly, it was in these many and varied art forms that wine was honored and represented from every angle: wine for mass, liturgy, religious celebrations such as christenings, the coronations of the kings of France, viticulture, winemaking, banquet service…

During the Middle Ages, wine was not only considered sacred, it was also consecrated as a work of art, not only because its production required a very precise know-how, but also because of its divine taste and the feeling of intoxication it gave to those who drank it. From then on, when famous people were visiting a town, it was up to the local bishop to offer the guest some of the region’s finest vintages. It was the French clergy’s fascination with episcopal vines that enabled culture to continue to develop in France, even as it was declining throughout Europe.

When poetry took over from the chivalric literature of the early Middle Ages, the representation of wine became even more pronounced in the descriptive arts of the Middle Ages (literature, lyric art…). I’m thinking in particular of François Villon, the first of the accursed poets, whose lyrical art was strongly influenced by wine from the 15th century onwards. Note the following verses:

“Everything to taverns and girls”

(Le Testament) and

“Vin perdtes maintes raisons”

(Le Grand Testament de François Villon). Of course, he wasn’t the only one, and we can also mention François Rabelais who, even if he wasn’t a cursed poet, didn’t fail to extol the merits of wine:

“Drinking is man’s nature, drinking good, fresh wine, and from wine, divine one becomes”.

or again

“Wine is the most civilized thing in the world”.

. These authors’ regard for wine is obviously reminiscent of the Greeks’ worship of Dionysus (and the Romans’ of Bacchus).

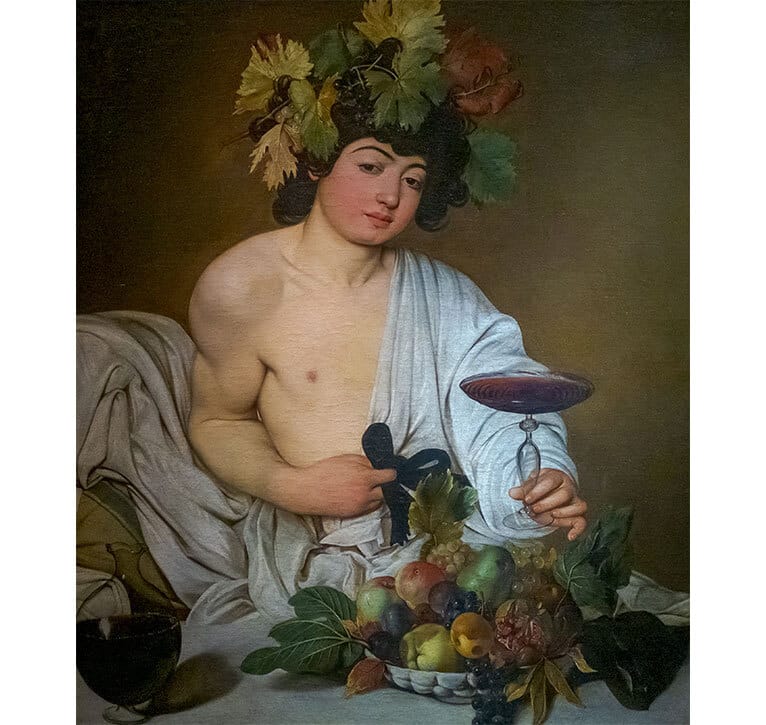

During the Renaissance, thanks to the discovery of the New World, the revolution in ways of thinking, the artistic revival with the introduction of perspective and the return of the Greco-Roman model in Florence, Medici, Venice (…), artistic representations of wine took on a new angle. It’s less a question of representing wine in its divine or elesiastical guise, but rather because of the intoxication and voluptuousness it brings to its consumers. Indeed, when Caravaggio painted Bacchus in the 1590s, it’s not so much the sacred nature of the god of wine that stands out, but rather the still life that characterizes this naturalistic scene, symbolizing the passage of time (the fruit and flowers in the field) and the evanescence of sensual pleasures (the naked body and the wine glass held in the fingertips like a trophy).

Detail of Bacchus by Caravaggio, oil on canvas, (1597-98). Uffizi galleries, Florence, Italy

Wine and art in contemporary times

The contemporary era begins between the French Revolution and the fall of the Napoleonic empire. It also coincides well with the gradual arrival of the Industrial Revolution. This period of great social, economic and cultural upheaval saw the resurgence of an artistic movement: the poètes maudits. Here, of course, I’m talking about Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud, Gérard de Nerval, Thomas Chatterton, Edgar Allan Poe… Plagued by a Parisian spleen that made them sadly unhappy to the point of deriving the darkest and most abundant artistic inspiration, these artists introduced psychotropic drugs and alcohol into their lives, of which wine was the most readily consumed. The symbolization of this state of mind can be found in Henri Fantin-Latour’s painting : Les poètes maudits (1872). He depicts these poets, hairy and bearded, looking empty, seated around a carafe of wine, the elixir of choice for these tortured personalities. As Arthur Rimbaud said

“The only thing unbearable is that nothing is bearable”.

With this in mind, unhappy people often turn to drink and intoxicating beverages to forget their woes.

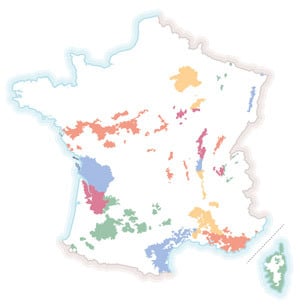

Let’s change the tone, and return to a slightly happier theme. Thanks to technological advances and improvements in wine bottle packaging since the 20th century, some châteaux have chosen to transform their labels into veritable works of art. For example, since 1945, Château Mouton Rothschild has had its labels designed by artists (or well-known cultural figures) to immortalize each vintage. These include collaborations with Jean Cocteau (1947), Salvador Dali (1958), Pablo Picasso (1973), Françis Bacon (1990) and Jeff Koons (2010). We can also think of the Trévallon estate, founded by Eloi Durrbach, whose parents were artists and close friends of Picasso. Having asked his father to design some fifty labels featuring geometric shapes in different colors (blue, red, yellow, green), Eloi Durrbach has since 1996 marketed only bottles under these artistic labels (he has been supported by his children since his death a few weeks ago).

Today’s vineyards are also places for art exhibitions of every kind. Many estates (large and small), for example, are places of architectural expression, allowing buildings with curved, artistic forms to flourish in the midst of vineyards and nature, creating a harmony that is as singular as it is inspiring. In the 1990s, for example, we saw the construction of a bioclimatic bubble house in Crozes-Hermitage, an artistic creation that combines tradition and modernity right in the middle of the vines in this prestigious terroir. The house is a tangle of composite bubbles that can be removed or replaced at will. In a different vein, some châteaux, such as Château Cheval Blanc, have decided to use the winemaking site itself, the winery, for innovative artistic expression. For example, the Cheval Blanc winery, designed by Christian de Portzampare in 2011, combines curves and depths in a snow-white ensemble, topped by a very green roof. From the air, you’d think you were looking at one of the ships from the next chapter of Dune, but you’re actually on the grounds of one of Saint-Emilion’s Grand Cru Classés, founded in the 15th century. In short, once again a work of art that sacralizes the harmony between tradition and modernity (as you can see, we’ve come full circle, back to the idea of the sacred).

Cover photo: GiorgioMorara – Stock Adobe